Stigma is stupid… And it’s killing young people

Opioid toxicity is the leading cause of death for British Columbians aged 10 to 59

What a terrible tragedy it would be, if just one fully loaded passenger plane crashed in British Columbia, causing the deaths of 300 people onboard.

Imagine the horror and outrage that would be expressed; the public outpouring of grief, the support and compassion offered to the bereaved.

Yet in just the first six months of this year, well over three times that number of people died of opioid poisoning in our province. Across the country, an average of 20 die each day.

In total, within just the seven years since BC declared a public health emergency due to opioid deaths, more than 12,000 have died here.

That’s 40 plane crashes, without the planes.

Here’s another perspective: More than half the seats in the lower bowl of BC Place Stadium could be filled by those lost to toxic drugs in this province.

More than half the seats in BC Place Stadium could be filled by the number of lives lost in this province over the past 7 years. Most were under the age of 60. Interior photo of a section of BC Place Stadium. (Photo: Christy Garcia)

It should be noted it will not take a further seven years to fill the stadium to capacity, because since 2016, the death rate has more than doubled.

Without a lot more support for substance users, “I feel we're going to lose out on a whole generation,” University of Toronto addictions health specialist Dr. Peter Selby said in a recent CBC interview.

In general, the horror, outrage and effective government response one would expect to be generated on behalf of these mostly young lives is strangely missing – especially when compared to Covid.

Those who died of the pandemic in our province numbered about 5,000. That’s less than half the total of toxic drug deaths.

For decades it was normal for Canadians’ life expectancy to just keep growing. But in recent years it has begun to decrease, Elaine Hyshka noted in a recent CBC podcast. Hyshka is an associate professor and Canada research chair in health systems innovation at the University of Alberta's school of public health.

This concerning change was not due to Covid, she explained, though that might be one’s first guess. No, statistics have made it clear that the vast majority struck down by Covid were people over the age of 80. It’s actually because of the thousands of young lives – more each day, each month, each year – being snuffed out by toxic drugs. Across Canada: 7,300 last year.

The magnitude of this crisis is breathtaking.

The lack of intense general concern in the face of such extensive human, social and economic cost is a travesty. Yet it does help bring into sharp relief the reach and weight and fatally oppressive power of stigma.

Due to this immense stigma against drug users, their deaths are largely ignored, and blamed on the victims themselves.

The families who mourn them – who knew them as whole, lovable individuals with character, skills and interests – often do not receive the normal and needed support and empathy or even condolences.

As if, when the cause of death is toxic drugs, a normal response to their loss is not necessary.

Stigma is so pervasive that many are not even aware of the way its tainted lens can erase the basic human value of tens of thousands of Canadians. Fortunate folks who remain untouched by this ever-compounding tragedy may believe nothing very important has been lost.

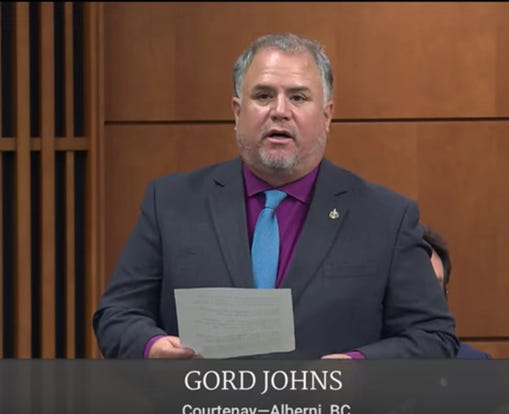

Gord Johns is one person whose eyes have been opened. As the Member of Parliament for Courtenay-Alberni since 2015, Johns has seen his Vancouver Island community hard hit.

Gord Johns, NDP Member of Parliament for Courtenay-Alberni in BC, speaking in the House.

He’s seen deaths from toxic drugs within his extended family, his circle of friends and acquaintances, and at every level of society, including community leaders.

It has greatly changed his point of view, which he described as initially closer to that of conservative leader Pierre Poilievre. Since then, his own losses and concern for his constituents led him to become a tireless advocate pushing the federal government to meet this crisis.

Government is “not acting with a sense of urgency,” he said in a recent interview. “They come up with excuse after excuse, blaming jurisdiction. But they didn't do that when Covid hit.”

As we all saw, the government’s pandemic response was quick to move past perceived barriers to deliver needed health service. Education, vaccine distribution, and reporting to the public were all included in its integrated approach.

“Where’s the daily reporting on the toxic drug crisis?” Johns asks.

When one understands the scale of this crisis, and the vast cost and effects on our society, it is shocking that compared to Covid spending, the money government allocates to the opioid crisis is less than one percent, he says.

Pandemic-related expenses were listed as $512.6 billion in last April’s federal budget.

In stark contrast, only $800 million has been spent on the toxic drug crisis since 2017.

Funding to strengthen the public health care system is set at less then $200 billion over the next 10 years. Of that, $25 billion is earmarked for “shared health priorities”, one of which is increasing access to mental health and substance use services and supports.

This past summer, Johns funded his own trip to Portugal, a country that took a radical and life-saving approach to its heroin crisis 20 years ago.

Earlier this year, doubt was cast on the Portugal model by several North American newspaper articles which inferred, among other things, that the country’s reforms are no longer working, that open drug use is rampant, and that people only go into treatment because the alternative is prison.

NDP MP Gord Johns, left, and Liberal MP Brendan Hanley met with officials in Portugal last summer to investigate services offered there to prevent harm and offer treatment for opioid users.

None of that is true, Johns found. “Portugal developed a national strategy, implementing all the pillars through a health-based [not criminal], integrated, patient-centred model.”

In fact, Johns says, the country even mobilized its army to build labs where methadone could be produced economically. That permitted Portugal to rapidly increase the number of people on methadone within two years, from just 200, up to an astonishing 35,000.

Portugal’s strategy decriminalized personal possession of illegal substances and made treatment available on demand -- often the same day the patient makes the choice.

No one is threatened with prison. Recovery, prevention and education are all included in the strategy, as well as a safe supply of substances. Portugal also offers tax breaks to employers who offer jobs to those recovering from addiction.

In 2021, Johns introduced Bill C-216 in Parliament as a private members’ bill. It included all of Portugal’s main aspects, which had also been recommended by a Canadian panel of experts.

The Health Canada Expert Task Force on Substance Use included representatives from First Nations, law enforcement, health experts, substance use experts, and people with lived and living experience.

Despite those experts’ informed and unanimous recommendations, the bill was defeated by the Liberals and Conservatives. Moreover, Poilievre has promised to end safe supply if he wins the next election, which polls currently suggest could be likely.

Meanwhile, “The Liberals continue to take an incremental approach in the middle of a health crisis,” Johns says. “This is costing lives.”

Yes. In fact, some time next year, the number of lives lost to toxic opioids since 2016 – when Canada began collecting data – is very likely to exceed the number of Canadian lives lost during military service in World War II.

By the end of Dec. 2022, 36,442 Canadians had died of opioid poisoning. If as many die this year as last year, the toll will rise to 43,770 by Dec. 2023.

Between 1939 and 1947 during WW II, 44,090 Canadians died as a result of accident, illness or injury while in service, or were killed in action.

The big difference is that opioid deaths could largely be prevented, given the political will and courage.

Why do people take drugs?

We all want to feel good. That simple human desire has fueled an enduring use of substances – for both pleasure and for pain relief – that has lasted through the ages.

In fact, the great majority of us take a little something to modify our moods or well-being, at least occasionally: to help us relax, to sleep, to have a good time, or to find some freedom from physical or emotional pain.

Then, however, if we become physically or emotionally dependent, continued use is necessary to prevent the misery of withdrawal.

As a society, we drink alcohol, smoke cigarettes, and pop prescription pills, as well as smoke, inhale or ingest ‘recreational’ drugs. Quite a few of us die from each of these things. Yet many depend unquestioningly upon their continued availability.

You might think all that would make us a little less likely to point fingers at one another.

But we do. Mostly we point them at opioid users. Whether it’s said out loud or not, many seem to believe the lives of drug users are not worth saving; that they deserve whatever harm may come to them, because they chose to take drugs.

That kind of stigma is based on ignorance of several truths:

1. Alcohol’s economic cost to society is more than double that of opioids

The Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction recently reported that alcohol use cost Canadians $19.7 billion in 2020, the most recent year studied.

Opioid use, in contrast, had a societal cost of $7.1 billion. And yes, its costs to society are increasing. But the report also noted that nearly 75 percent of the economic costs of opioids are from lost productivity: “…

more specifically, [from] people dying at an early age from opioid use.”

The economic costs to society include health care, policing, courts and prisons, and lost years of productivity, both from imprisonment and from premature death.

(Photo: Image by LipikStockMedia on Freepik)

Of deaths caused by substance use in 2020, “Alcohol and tobacco account for over 85 percent of deaths alone,” states Emily Biggar, CCSA Research and Policy Analyst and a researcher on the project.

The report shows the huge impact of all substance use on both the healthcare and criminal justice systems, she noted.

Importantly, it also greatly affects the ability of people to work and contribute to the economy.

“Initiatives across the spectrum of prevention, harm reduction and treatment are needed to improve the health and productivity of people in Canada,” Biggar added.

2. Opioids were once in common, widespread use.

Despite the current stigma around opioid use, about a hundred years ago, it was pretty normal for people to use a bit of heroin, morphine, or cocaine. These drugs were legal, and were considered safe and medicinal.

People could buy them at their local drugstores. They were used as ingredients in medicines and cough syrups, such as the popular “Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup” which contained morphine.

Even Queen Victoria reportedly enjoyed a bit of opium now and then, as well as Vin Mariani, a wine made with cocaine. Other fans of the same wine included Ulysses S. Grant, Thomas Edison, and Pope Leo XIII. None of those names have been remembered in history as addicts. Many know that the original recipe for Coca Cola contained a form of cocaine.

Pope Leo XIII enjoyed Vin Mariani, which contained cocaine. He said he kept the wine handy, to “fortify himself in those moments when prayer was insufficient.” He also created a special Vatican gold medal which was presented to the manufacturer “in recognition of benefits received.” (Photo: Wikimedia)

These drugs were inexpensive, easily available, and widely used. People were not looked down upon for using these medicines. There was no stigma.

However, the same was not always true of alcohol. Unlike opiates, drinking was seen as a direct cause of many social problems: violence, accidents, domestic abuse, and family poverty.

For those reasons, many people did judge and condemn those who drank. In fact, over a period of about 20 years, alcohol was prohibited in much of North America.

Prohibition did not prevent alcohol from being made and consumed, however. Much of the ‘moonshine’ back then was stronger than even the hardest liquor we could buy today. (In the same way, declaring opioids illegal did not eliminate them, and instead saw them become far more potent and dangerously available.)

A police raid in 1925 destroyed 160 kegs of illegal alcohol in Elk Lake, Ontario

Alcohol was prohibited in various parts of Canada and North America. It was seen as “an obstacle to economic success; to social cohesion; and to moral and religious purity,” says the Canadian Encyclopedia.

Now, of course, we can legally buy a range of alcoholic beverages, from mild to strong — as much as we want and can afford. These beverages are made to legal safety standards with a reliable and consistent percentage of alcohol, and are offered in ‘safe consumption sites’ like bars and restaurants. Alcohol, tobacco and cannabis can all cause harm, but are freely offered for sale under government regulations.

Drunk drivers still cause deaths, of themselves and others, and alcohol is a frequent factor in murder-suicides and other violence.

But opioids are condemned. Those who use them are stigmatized. They are mostly available only illicitly. They can be fatally strong, and too often contain other drugs or poisons that can also kill.

3. Many opioid poisonings occur in middle or upper class homes

People who hold responsible positions also use drugs – though that rarely becomes public knowledge. Family and friends may have had no idea the person ever used drugs before they died.

Farther down in this article you can read more details about a few of these people, and their families. Those who make public statements about the true cause of death are to be commended for their courage to speak the truth, despite the heavy stigma.

4. Once one’s body becomes dependent on a drug or alcohol, ‘choices’ diminish to when, not whether, it will be used, as withdrawal makes people very ill.

Guy Felicella describes opioid withdrawal as “the flu, times 10… Something so terrible that you’d do anything to stop feeling it. Including using the same drugs you’re so desperately trying to get off of.”

The vast majority of people need significant help and resources to recover from addiction. Yet good help is desperately hard to find. Far too many who wanted help died while waiting for their names to move to the top of the list.

Waitlists for detox and treatment take weeks or months.

During the 2008 court case about Vancouver’s first safe-injection site, BC Supreme Court Justice Ian Pitfield agreed that addiction is an illness, not a choice:

"The original personal decision to inject narcotics arose from a variety of circumstances, some of which commend themselves to choice, while others do not,” he said.

Justice Pitfield acknowledged that traumatic life circumstances such as neglect, loss, and physical, sexual or emotional abuse can make people more vulnerable to addiction.

He added: "However unfortunate, damaging, inexplicable and personal the original choice may have been, the result is an illness called addiction." He concluded that not only was the safe injection site helping people who had an illness, but also that it was delivering needed health care.

We tend to think those who are addicted could simply choose not to be. Though we don’t expect people with any other serious illness to simply choose otherwise. Nowadays waitlists are increasing for cancer treatment as well, but medical treatment is always offered to restore them to health. If that is not possible, they are offered palliative care.

Opioid addicts, however, may be treated with disgust, disrespect and disregard for their physical and/or mental well-being, even by medical professionals or by their own loved ones.

Stigma causes great pain. It can and frequently does prevent people from asking for help. It can sabotage their efforts to quit if they feel they may be branded as addicts.

In fact, one Holocaust survivor said the worst part of his experience at Auschwitz was the deliberate humiliation, being treated as someone less than human – “like a louse, a bed bug, like a cockroach” – in his case because of his race and religion.

Humiliation, which can be defined as lowering a person’s status, especially in front of others, is used as a tactic in war and torture.

But stigma is also being used to dehumanize hundreds of thousands of Canadians as less than human, without value, worthless… or ‘zombies’. Clearly there is no urgency to save the lives of those one defines as the walking dead.

It has indeed been horrifying to see the intense and increasing level of public drug use.

But the apparently catatonic individuals we see are under the effect of powerful drugs. It is not a permanent state. And due to the increasingly potent street supply, they are at high risk of death from widely varying levels of fentanyl. As if that wasn’t enough, any of a handful of other harmful chemicals such as benzodiazepenes may be included in the mix.

There is no need to give up on even those who appear catatonic. Rampant and increasing homelessness has not only made this problem more visible, but has also worsened it.

Life on the street is not safe or fun. One woman interviewed on a news program said it was like living in hell. Can we blame homeless people when they seek a bit of peace or comfort in a cheap and highly accessible form?

Even young people who are housed may be struggling with economic despair, or the mental burden of climate anxiety and fear of what the future will bring.

Given affordable homes to live in, available and effective treatment, and a safe and regulated drug supply, our streets would not look like a horror show. Most of the ‘zombies’ could be brought back to life – and could contribute to the very society that is letting them down so completely.

All models of this airplane in the world – the Boeing 737 Max 8 – were grounded after two crashes in 2018 and 2019 killed a total of 346 people. (Photo: acefitt, Wikimedia)

Is addiction worse than death?

Studies in Switzerland and the UK have shown that people who are addicted to opioids, but have access to a safe, consistent supply, can still live productive lives. They can hold jobs and participate in their families.

Given that stable support, many ended up voluntarily reducing their drug use. Some were able to discontinue it entirely.

So perhaps addiction is actually not worse than death, as some doctors and right-wing politicians seem to want us to believe.

In fact, experts say that the vast majority of substance users are not addicted.

It’s important to note that this means the visible addiction we see on the street is truly only the exposed tip of an enormous hidden iceberg of potential toxic drug deaths.

“We know from BC and other areas that a substantial proportion of people that die, potentially upwards of 30 percent, don’t have a history of opioid addiction or drug use disorder. And they need support too,” says Professor Hyshka.

Karen Ward, a drug policy consultant with the City of Vancouver, agrees: “The vast majority of people who use drugs just do it a once in a while," she says. They use drugs in the same way that most of us may have a few occasional drinks.

Moreover, with the right support and resources, even longtime drug users have beaten addiction and gone on to contribute greatly to society.

Guy Felicella, for example, a frequently interviewed harm reduction advocate, found his way to recovery after 30 years of drug use, starting at the age of 12. Twenty of those years were spent homeless in Vancouver’s notorious Downtown Eastside.

Guy Felicella in earlier years, when he was homeless on the Downtown Eastside.

Guy Felicella at present. (Photos submitted)

Yet Felicella is now married, has three children, and works as an educator, consultant, and motivational speaker.

At this point, BC is on track to lose at least another 2,200 people next year – most likely, all of them loved, with families who are depending upon their continued existence.

The number of minors who died under the age of 19 has tripled during the same time period. Thirty-six youth died of opioid poisoning last year in BC.

Even wealthy and successful people can die of opioid poisoning

Because drug use on the street is so apparent, it’s always easy for media to report and photograph. Unfortunately, this means that the general public gets a distorted impression that those who die of drugs are mostly the homeless.

Far from it. Those who have died of drug poisoning in recent years include the following:

- In 2016, Steven Diamond, a Vancouver massage therapist, addiction counsellor and member of a wealthy family, died of fentanyl poisoning while on a waitlist to see an addiction psychiatrist. His sister, Jill Diamond, said her 53-year-old brother had both professional and personal knowledge of addictions treatment systems, and also had his philanthropist family’s financial support.

Still, she said, “The fact that even he couldn’t get well, despite giving his entire life’s effort, shows addiction is a disease that must be looked at medically with new models of care.”

Steven Diamond (Photo submitted)

Like many families with fewer resources, she noted that his search for help ran into, “at every turn – delays, disappointments, and wait-lists.”

In June this year, his family donated $20 million to the St. Paul’s Foundation. Along with a commitment of $60.9 million from the province, the money will help fund the hospital’s Road to Recovery program, which aims to shorten wait-lists and provide support to patients through a full spectrum of treatment services in one location.

“Some people say the system is simply broken. But the truth is, the system we need doesn’t even exist,” Jill Diamond said. Her words refer to the same heartbreaking roadblocks and utter frustration many families face in trying to find help when their loved ones need it.

- Similarly, many roadblocks prevented a Victoria family from saving their 16-year-old son before he died of an overdose in 2018.

Victoria dentist Rachel Staples told an inquest that she and her husband Brock Eurchuk would have been willing to spend a million dollars on treatment for their son Elliot, but they were unable to find real help. Since their son’s death, Staples has worked with others to raise funds to establish a unit for youth mental health and substance use treatment at Victoria General Hospital.

It will be the first youth treatment unit on Vancouver Island. The lack of such a treatment facility was just one of the problems the family faced.

Elliot Eurchuk at 15. (Photo submitted)

- A Thompson Rivers University vice-president was found to have died of an accidental overdose during a visit to Victoria in 2017. Christopher Seguin was 39 and married, with two children. In his youth he had been a varsity football player at SFU, followed by a job at SFU.

Two years earlier Seguin was honoured for his extensive volunteer work with a BC Achievement Award. Among his many accomplishments, Seguin had helped raise funds for research, capital projects and student assistance, resurrected the Kamloops marathon, founded an annual music evening, was a director and instructor with a leadership program for at-risk youth, and was an active Rotarian who helped introduce community dinners for low-income families.

Christopher Seguin, shown here with members of the Kamloops Hindu Cultural Society, had been honoured for his extensive community volunteer work (Facebook)

- Also in 2017, a widely known and respected Buddhist meditation teacher, Michael Stone, died of a fentanyl overdose in Victoria. His family said his bipolar disorder had been worsening and that he was likely trying to self-medicate. He had reportedly been able to manage his illness for years with meditation, exercise and careful diet. When he started having problems, he turned to the medical system for help. But it wasn’t enough.

Stone had called a substance use and addictions pharmacy earlier in the day, “likely to ask for a safe, controlled drug to self-medicate," his wife, Carina said in a prepared statement. But sadly, "he was not a candidate." He was found unresponsive that evening and later died. Stone was a father of two, with another on the way. He was mourned in vigils across North America and beyond.

Buddhist teacher Michael Stone (Photo: Maggie Jane Cech, Facebook

- In 2019, a popular hockey writer and broadcaster also died of cocaine and fentanyl poisoning, though it was initially thought to be a heart attack. Jason Botchford was 48 years old and married, with three small children. When the cause of death was confirmed, his wife Kathryn released a statement saying: “We were completely shocked and in disbelief to discover the cause of Jason's sudden death.” She described him as a good husband, an “incredibly hands-on Dad”, and a loyal friend and colleague.

Jason Botchford with his wife Kathryn and family. (Photo: GoFundMe)

She added, “The cause does not change who Jason was to all of us, but just makes his death that much harder to comprehend." His loss was deeply felt by journalism colleagues, longtime readers, and the Vancouver Canucks, whom he had reported on for more than 10 years.

In a speech Kathryn gave about stigma earlier this year, she said: “I feared that people would treat my children’s loss of their father as insignificant, because of how he died. It was in those moments that I realized how much shame Jason must have carried, and why he hid his substance use from everyone.” She added that the coroner told her it was relatively common for middle-aged men to hide their substance use, as her husband had.

Some health care workers, such as pharmacists, dentists, doctors and nurses, have relatively easy access to opioid medications. Front-line health care workers in particular have been under intense and increasing stress for years, in jobs where they may deal daily with terrible injury, death and intense emotions of patients or families.

Some succumb to the temptation to use the same potent medicines they dispense, despite the risks and safeguards. It is estimated that 10 to 20 percent of health care workers may suffer from addiction. But because they have access to regulated medications which allow them to depend on a consistent potency, they rarely overdose and can avoid poisoned street drugs. We rarely hear about them in the news.

It's estimated that 10 to 20 percent of health care workers may have substance use disorder. Photo: Pavel Danilyuk

Several American professionals have spoken out about their drug use in efforts to reduce the shame of stigma for others. Among them is a professor of psychology who works at Columbia University, who is open about his regular recreational use of heroin and other drugs.

Another is Dr. Peter Grinspoon, who became addicted to Vicodin in medical school, and used opiates for the next few years until the police showed up at his office one day.

Dr. Faye Jamali, an American physician and ‘soccer mom’, rarely drank and had never used recreational drugs, but became an injection opiate user. An injury and two surgeries had left her overwhelmed by pain. She found that the prescribed Vicodin didn’t only reduce the pain, but also her stress. “The meds seemed to make everything OK.”

When her colleagues became suspicious, she was suspended from her job. Jamali told her story in the hopes of helping others who might be suffering, because the shame caused by stigma prevents them from getting the help they need.

Jamali was able to return to work after treatment and weathered personal crises, including breast cancer, without returning to opioids. “I learned that if I do my recovery daily, I can have an amazing life. In fact, a much better life than I did before.” She believes that if it could happen to her, it could happen to anyone.

Politicians too are not immune to drug use. Even way back in 1978, a widely read American magazine alleged that cocaine and other drugs were used by Washington politicians.

One powerful U.S. senator, Joe McCarthy, was reportedly addicted to morphine as well as alcohol. When Harry Anslinger, the architect of the U.S. ‘war on drugs’ discovered McCarthy’s addiction and threatened to publicize it if McCarthy didn’t quit, the politician refused. Instead, to protect government’s reputation and security, Anslinger ended up arranging for a local pharmacy to provide free legal narcotics, up until McCarthy’s death in 1957 – when he was still a working senator.

Former Toronto mayor, Rob Ford (Photo: Facebook)

In Canada, many may recall that former Toronto mayor Rob Ford entered a treatment facility in 2014, after news hit the media that he used crack cocaine. Among his fellow clients there, the millionaire told a reporter that one was a professional athlete, and another was a ‘captain of industry.’ Ford passed away two years later of cancer.

(Cocaine is a stimulant, not an opioid. However, a portion of the street supply of cocaine, crack, meth, and most other ‘recreational’ drugs is tainted by fentanyl. It is very likely that many of those who die from it had no idea they bought fentanyl.)

What is stigma?

One dictionary defines the word stigma as: “a strong feeling of disapproval that most people in a society have about something, especially when this is unfair.”

To illustrate the point, it notes that being divorced or being an unmarried mother no longer carries stigma. Not so long ago, it was also against the law to have sex with a person of one’s own gender.

It should be obvious from these examples that stigma is stupid – it is not based on truth, but on unsubstantiated prejudices that change with the times. It makes no more sense to shame people who use opioids than it did to shame those who smoke or drink alcohol.

Stigma may not make sense, but it is also powerful enough to kill. The fear of being shamed and blamed forces people to hide their drug use from their friends, families, employers, and even their doctors.

Kathryn Botchford, who lost her sportswriter husband Jason to a fentanyl overdose, said the dehumanizing effect of stigma forces substance users to keep the problem secret. And it is those who use alone, in secret, who are in the greatest danger of dying.

The very real stigma against substance users also prevents governments from addressing opioid poisoning as the single biggest threat to the lives and health of youth and working-age adults now in Canada.

Politicians fear losing an election if they are thought to be too soft on addicts or substance users. Stigma tells us these people are criminals; not worth any added expense.

Unfortunately, the important fact that many who die are not addicted, but use substances on an occasional or recreational basis, is lost or conveniently ignored.

Thousands of well-loved, active family members, valued employees, even leaders in their communities, are being lost to society through the perpetuation of stigma.

Guy Felicella posed recently in the Downtown Eastside with about 25 others who are in recovery from opioid addiction and now work in jobs similar to his. (Photo submitted)

Upon his return from Portugal this summer, MP Johns was asked what he found to be the most exciting aspect of the work being done there on opioid harm reduction. His response referred to something that should be unremarkable, yet seems so far from possible in this country, at this time.

It was the fact that in Portugal, all political parties agreed to be led by experts’ guidance.

“They put their gloves down,” Johns says. “They said ‘We're not going to influence this. We're going to let the experts guide us on our way out of this.’”

Over the 23 years since the Portuguese strategy was initiated, power has moved back and forth between the parties. But both sides retained the drug strategy. Both sides knew it worked.

During his visit there, Johns says he met no officials or citizens who thought it would be wise to end any part of the plan.

Yes, he said, homelessness has begun to cause some open drug use there, as it does here, but only in Lisbon, the largest city. He says parties agree that any other problems have been caused by the long-term effect of budget cuts during a period of belt-tightening.

In the 1990s, former Vancouver mayor Philip Owen asked his council to consider opening a safe injection site. “Just think about it,” he said at the time. “Think about the country. Leave politics at the door.”

Though he was a member of the conservative NPA party, Owen had begun to see the wisdom of acting to save lives. Political advisors warned him that his actions could cost the next election. They were wrong.

He won the next two elections handily. Insite opened, and life expectancy in the Downtown Eastside increased by 10 years – a rare accomplishment.

Perhaps the government that does take effective action to halt the carnage of Canada’s opioid crisis will be similarly favoured with election victory… should they find the courage to try.

As Kathryn Botchford says, “We all have the responsibility to change the narrative on substance use.”

Stigma is stupid, and it is killing far too many young people.

Thank you for such a well researched, heartfelt and deeply compelling post, Grace. I found it very readable and am SO going to share!

Now THAT is an eloquent, well-researched, perceptive article. Brilliant work, Grace!